Drying Colorado River and 40 Million Reasons to Do Something About It

The drying Colorado River has received widespread media coverage because of the disruptions it is experiencing, as climate change alters the historical patterns of temperature and rainfall.

It was quite the headline in 2014 when the Colorado River made it to the ocean for the first time in more than one and a half decades. The river, which supplies fresh water to around 40 million people, has been diverted through dams and farms along its path, so much so, that it hardly ever gets to the ocean.

In recent years, the river has received widespread media coverage because of the disruptions it is experiencing, as climate change alters the historical patterns of temperature and rainfall.

As the effects of climate change tear through the world, millions of people living who depend on the drying Colorado River are getting front row seats to see this horror flick. Unfortunately, unlike a Hollywood thriller, this show doesn’t end after a couple of hours. The threat of the Colorado River drying up as a result of climate change is real.

According to recent research, the 1.4 degrees increase in temperature seen in the region over the last century has caused an 11% reduction in the annual amount of water flowing through the river. As global warming worsens, the Colorado River could gradually fail in its capacity to support the region’s freshwater needs.

The impact of global warming on the Colorado River is a major concern because it is the lifeblood of the South Western United States. Here are some facts:

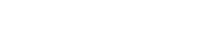

- The Colorado River is the primary source of drinking water for around 40 million people in Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado and California

- Water from the Colorado River irrigates more than 4.5 million acres of farmlands in the region

- More than 30 endemic fish species live in the river, and it also supports millions of birds

- The river powers the Hoover and Glen Canyon dams, generating enough power to supply 1 million families.

- The recreational impact of the Colorado River: more than $260 million every year for the tourism industry

- It is the primary water source for Lake Mead and Lake Powell

It is no surprise, therefore, that more groups and state governments are waking up to the need for more urgent action to preserve the river.

Decades of Warming Temperatures

Although overuse played a part in the dropping levels of the Colorado River and the reservoirs depending on it, the drought which started at the turn of the millennium is the chief reason for the substantial decline in the river flows. Even though drought is majorly caused by a lack of precipitation, research shows that at least a third of the decrease in flows is closely linked to decades of warming temperatures in the Upper Basin of the Colorado River as a result of climate change.

Between 2000 and 2014, temperatures in the Upper Basin rose by 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit more than the average in the 20th century. The high temperatures have persisted till date, creating what is called the hot drought.

High temperatures affect the levels of water in the Colorado River in various ways:

- High temperatures lead to extended growing season, causing more water demand from plants. When combined with faster melting of snow, this reduces the water flow to the river.

- Apart from increasing daily water consumption by plants, high temperatures increase evaporation from water bodies and soils (by up to 4% per degree Fahrenheit) leading to less water flows into the river.

With this situation, water levels in Colorado River, and by extension, Lake Mead and Lake Powell have been dropping consistently over the last few years. Both lakes were at full capacity in the year 2000. However, by 2004, they lost enough water that could have supplied California with its legal share of the Colorado River water for five years. To this day, the lakes are still struggling.

As of September 2018, Lake Mead was only 38% full while Lake Powell was 48% full. The wet winter of 2019 brought some much-needed respite (in comparison to the last 20 winters), but it was only enough to increase Lake Mead and Lake Powell’s capacities by a mere 2% and 5% respectively.

The Seven States That Rely on the Colorado River

As it stands, the rising temperatures are threatening water supplies to the seven states that depend on the Colorado River: California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The governments of these states, past and present, have continually wrestled for control and management of the river’s resources and the reservoirs it powers, often ending in temporary sharing deals.

The latest of such deals, the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) {PDF}, was signed in March 2019 to prevent the government from enforcing any federal water use restrictions and trigger more severe control measures. As part of the deal, states like Arizona and Nevada agreed to reduce their annual water allotment by 7% and 4% respectively.

Will this be enough?

Federal water managers are already looking for new ways to wade into the arrangement made by the seven states by pushing for a new agreement (separate from the DCP) to replace the 2007 Pact from the year 2026.

The drying Colorado River and Arizona farmers

Arizona farms contribute melons, beans, corn, greens, beef, milk, cotton and hay for use across the U.S. This is why agriculture is the largest consumer of water in the state. Some farms use as much as 8 feet of water per acre each year.

Under Arizona’s plan to stay in line with the DCP cuts, farmers now face a 60% cut in their share of water from the Colorado River for the next three years. After this period, access to the water supply could be cut completely.

To deal with the situation, farmers around Arizona, including the #Maricopa and #Pima counties are collaborating with irrigators to deepen groundwater wells and the state will provide $30 million to help with this.

Additionally, some farmers are already mapping out farmlands that will be left to lie fallow. They expect that in the coming years, more than a third of the farms in Arizona will be empty as more people heave themselves out of farming as a result of the ever-increasing costs of irrigation and apparent diminishing returns.

Las Vegas thirst for water

Las Vegas transformed quickly from a desert into one of the biggest cities in the country in just a few decades. Today, however, it is also reeling under the impact of the dropping water levels of the Colorado River. In the mid-2000s, the city started turning to neighboring counties to quench its thirst for water that can no longer be sustained by Lake Mead alone. This continues to date.

In 2012, the state engineer for Nevada approved plans by the Southern Nevada Water Authority to claim 84,000-acre-feet of groundwater from White Pine and Lincoln counties. Both counties only have a population of 15,000. This made them a prime target for the state’s thirst-quenching drive.

In 2015, Las Vegas completed work on a three-mile-long tunnel designed to suck even more water from an already depleted Lake Mead. They expect the tunnel to continue delivering water long after the reservoir has fallen below a point where it can no longer power the Hoover Dam.

At the current rate of depletion of the water levels in the Colorado River, Las Vegas is still likely to run out of water in under three decades even with these unusual efforts to stay afloat.

The city’s economy in the future is dependent on a more responsible approach to its water usage. To avoid a future water catastrophe, businesses, residents and the local government will have to work together to create a sustainable road map to managing the city’s thirst for water.

Lake Mead, Tourism, and Small Businesses

With more than 7 million visitors per year, the Lake Mead National Recreation Area is the 6th most visited National Park in the US. The visitors inject more than $260 million into the local economy, keeping 125 small businesses and 3,000 jobs afloat.

Unfortunately, the decline in flows from the Colorado River and the bathtub ring formed around Lake Mead following dropping water levels has made the area less attractive to visitors. If water levels continue to fall, analysts expect the number of visitors to drop by 50%. If the water drops to 1,000 feet, the economic loss for the area could erase the $260 million revenue.

The trend of declining visitors started in 1996, coinciding with the start of the drop in the water levels. Other factors such as the state of the economy as well as growing negative coverage of the water situation have exacerbated the issue.

The receding waters also mean additional costs for some of the businesses in the area, forcing a number of them to further dip into their decreasing resources. The National Park Service is not spared either. The agency has invested more than $36 million to improve access following declining water levels, and they have another $5 million budget to handle future changes. If the water level drops lower than 1,060 feet, that budget will have to be increased.

Moving Forward, Turning the Tide

The climate is changing rapidly around us, at a pace faster than many studies predicted. The intense heat waves and extreme storms are just some of the visible impacts of global warming. Unfortunately, it has far-reaching effects in other areas of our lives.

Climate change is causing heightening insecurity to lives and livelihoods around the globe. Chuck Hagel, former U.S. Defense Secretary, once called climate change “a threat multiplier that will intensify hunger, poverty and conflict.” With each passing day, that weight of that statement comes to the fore.

Will humanity change course by drastically reducing emissions, saving energy, managing resources better, acting against forest loss and demanding more action from governments at every level?

As the Colorado River creaks under the weight of supporting 40 million lives, will there be goodwill from governments and institutions around the globe towards taking action to preserve water supplies for future generations? Perhaps it is time for everyone benefiting from the river’s resources to stand and be counted in the fight against the growing effects of climate change.

Maybe governments need to offer their citizens more incentives for efficient water use, reuse, and conservation. Maybe by doing so, Colorado River will continue to power the lives of millions in the decades to come. Perhaps we will not need to figure out what happens next when the river runs dry.

Augurisk is an innovative platform for climate change risk assessment. We also offer assessments for natural hazards and societal risks. Is your home or business at risk? Get a free risk assessment at Augurisk.com.